7 Things I Have Learned From the Mask of Freedom

Words + Non-fiction

2011.06

Cairo, EG

On the 26th of May, 2011, I was detained by Egyptian Military Police for fly-posting the sticker pictured to the left.

Luckily, I was released on the same day with no charges whatsoever pressed by Military Prosecution. This, I believe, came as a result of quick and vast external pressure that manifested from the internet community, human rights groups, the press, and well, phone calls certain members of the military had received from “people high up.” Throughout this process, I happened to learn a few things.

1) We are our biggest enemies.

Many people I know would like to believe that my detainment by Military Police was part of a military crackdown on freedom of expression and general civil dismay towards Egypt’s so-called interim military rule. In all actuality, my detainment was a result of a long-lasting civil crackdown on freedom of expression.

The way it all went down was, as I was sticking one of the stickers onto a lamppost, two civilians stopped me and expressed their discomfort with it. This led to a little debate which other passersby felt the urge to partake in, which very quickly led to a big scene that involved a lot of shouting on the corner of a crossroads of two main downtown streets. This prompted the close-by traffic officer to use his walkie-talkie to call in Military Police. The reason Military Police was involved was that the regular law enforcement apparatus was entirely dysfunctional following “the revolution”, and martial law was virtually put into effect.

This, I think, highlights the core problem we face as a nation, and that is the culture of righting the wrong wrongs, and wronging what could be legitimate rights.

For example, it seems very acceptable in our culture to keep someone from expressing an opinion you may not agree with, but it isn’t so popular to keep someone from throwing trash on the street or blasting the volume of a Vespa-mounted stereo. This is especially odd to me, because it would seem to me that the act of throwing trash on the street would cause more direct discomfort to a another person than a sticker that criticizes the country’s governing body.

Some would disagree with me and point out that if such criticism were left unchallenged, it would lead to even more popular dismay towards the military body, which could possibly spark mass protests and strikes, which in turn could lead to a political situation that would make your lifestyle quite uncomfortable.

This very unrealistic roundabout argument can easily be invalidated by the facts surrounding my detainment. Although the Mask of Freedom was originally unleashed upon the inter-web on May 19th, it only spread on May 26th within hours of word of my arrest spreading across social networks. It very quickly got picked up by Al Ahram Online, Al Shorouk News, The Daily News Egypt, The Christian Science Monitor, and even television (local and CNN). As a result of my arrest, the image was vastly spread in less than 24 hours. The irony is that the very image that the civilian halted me for, to keep me from spreading, garnered even more exposure only because he stopped me.

More importantly, did the spreading of the image negatively affect that person’s life? I can assure you, this person very likely wakes up in the same bed, eats the same food, and most probably has the same job. Knowing so, I wonder if he still thinks it was worthwhile to keep me from putting up those stickers.

I sincerely believe that if he would instead put that same energy into keeping someone from littering the streets or chronically honking a car horn, his life would instantly improve, and he would most certainly feel the difference.

2) We are all but vessels.

A couple of friends of mine were putting up the same sticker in a different part of town when they, too, were halted by civilians. As the crowd of civilians grew, my friends were accused of being foreign spies, plotting against the nation, disrupting the peace, and all kinds of emotionally-charged things, until finally a police officer showed up, examined the sticker for 30 seconds before saying “What’s the big deal? Freedom.”

What was a very vocally disgruntled crowd less than a minute ago all of a sudden proceeded to face my two friends with smiles and ask if they could have some free stickers.

So this raises the question: Were they against the sticker because they morally believed it was wrong, or simply because they felt the need to take it upon themselves to do what was socially perceived as right?

I think the latter is correct, because if they had truly believed in the righteousness of their cause, they would’ve firmly opposed the police officer’s ruling. They didn’t and that gives me the impression that this urge to censor the sticker comes from a less-entrenched external source than moral intuition. This is essentially true, as it is no secret that the military has been using state TV and official newspapers to propagate the importance of the military’s role as authority in the country, and spread paranoia in regards to “foreign agendas” and peace-hating troublemakers.

This is a clear indication of how we, as people, are so easy to sway based on the ideas we are fed. As such, the direction taken by humanity at large is frighteningly easy to control. Which brings me to the next point.

3) We all need a crusade.

I was having a chat with film director Amr Salama the other day about this notion of humanity as an easily controllable vessel. I told him how I imagined a world where all these very influential media resources used to propagate fear and paranoia would instead be used to promote things like empowerment, liberty, honor, dignity, creative freedom and social justice. Salama argued that tapping into humanity’s dark side is a lot easier than tapping into humanity’s bright side. Upon examining historical events, this theory becomes eerily true. Peoples’ conviction with things such as racial or sexual equality has been moving at a much slower pace than peoples’ tendency to fear and attack a race or unfamiliar culture.

Essentially, people will always need a crusade. Even when attempting to sell the idea of doing something inherently good, it will need to be packaged in a fear-driven crusade for it to work. It’s easier for people to be against something than for something.

For example, the only way to get masses of people to care about the environment would be to promote the fear of global warming. People are driven by being against environmental destruction, rather than being for environmental prosperity.

![]()

4) It is important to transcend from the digital to the physical.

There is great value in spreading ideas over the internet, even if these ideas remain represented in the digital dimension of the world. As long as these ideas are exposed to people, these ideas will have great value. However, as soon as an idea takes on a more physical form, its impact on unsuspecting viewers enormously multiplies. This is apparent when comparing between the impact of the Mask of Freedom on May 19, when all I did was post it online, and its impact on May 26, when I decided to go down and take it to the streets.

![]()

5) Niceness does not necessarily mean goodness.

They were very nice to me at the military’s prosecution headquarters. I was served soda, Nescafe, and engaged in conversations with smiling military men. The content of these conversations, however, made it very clear to me that these people do not usually act out of goodness, but quite the contrary. An example would be when they attacked the tents in Tahrir and pulled out men and women who might’ve allegedly engaged in sexual activities, the military’s actions seem to have been motivated by a kind of malevolence, rather than doing a good deed. The same arguably applies to when they arrest criminals. It seems to stem from the desire to beat the shit out of someone rather than simply keep someone from committing a crime.

I got this sense when discussing widely agreed upon basic human rights that these officers find to be absurd. They find it absolutely legitimate to cuss and slap-around criminals during their arrest rather than limiting the act of the arrest to simply making the arrest. I find this completely disturbing, because as military personnel, one would expect them to have an understanding of these sort of rights that would not only apply to civil criminals but even prisoners of war. But respect for other human beings is not why people take to having a gun for a living.

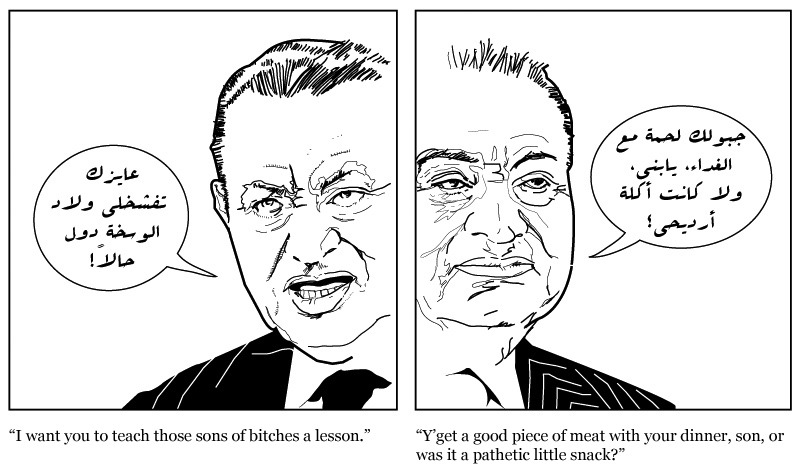

However nice these men may be, they do not act upon goodness. The same could apply to a man like Mubarak his, who is said to be quite nice and personable around those he speaks to. His actions as a 30-year-long ruler of Egypt, on the other hand, show him to be anything but “good.”

![]()

6) Old men in uniform will never understand young boys in shorts.

I won’t get into the absurdity of my shorts and long hair being a topic of debate and discussion among the Old Men in Uniform, but I would like to point out how baffled these men were by the involvement of a young man in activities that were not backed by “organizations” or power-driven aspirations.

One of the questions directed towards me during the friendly interrogation was whether I was a member of the 6th-of-April Movement or Revolutionary Youth Coalition. When I answered that I was part of neither, the next logical question they asked was if I had been paid by someone to put up the Mask of Freedom stickers across town.

These Old Men in Uniform clearly cannot fathom the idea of a someone going around town to express something backed by nothing other than personal motivation. Sometimes young people tend to do things they believe in with no aspirations for power, money, or fame. The fact that these men do not understand that, I feel, is very dangerous and quite sad.

7) The Military “manages.

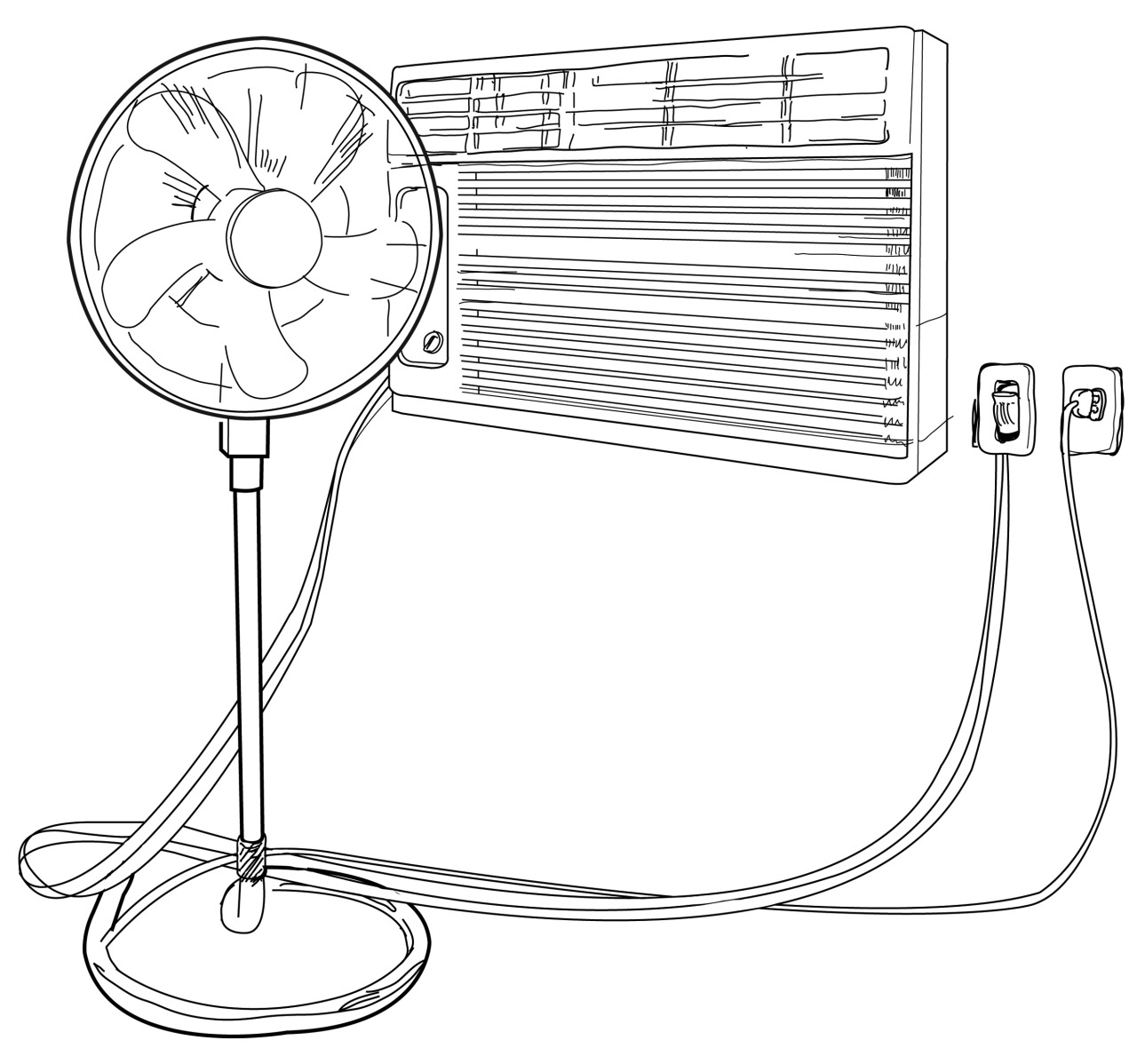

When debating whether or not the military is fit to “rule the nation,” a common argument brought up is that the military knows how to “manage”. It simply knows how to deal with situations. This very notion was made clear to me when inside the office of a high ranking officer at Military Prosecution Headquarters, I couldn’t help but notice the… air conditioning unit.

Yes, the air conditioning unit, which was an old model dating back to… maybe the late 80’s or early 90’s, was working very well. The room was definitely cool, but in accomplishing that, not only did we have to deal with the loud clunky noises of what sounded like a very exhausted machine, but the officer had set up a fan right in front of the unit to better spread the cool air around the room.

So instead of properly fixing the air conditioning unit or installing a more up-to-date device that might sound quieter and efficiently distribute the cool air around the room and most likely require less electricity to do its job, the army people thought it would be more practical to use the old unit and consume more electricity on the additional fan while at it.

![]()

This, I feel, has been the military’s strategy in managing the entire country since the Liberated Officers’ coup of 1952. As long as things work, regardless of inefficiency or social/psychological discomfort, they let it be.

Which is exactly why military personnel should be stripped from anything involving government.

--

[ The text on the sticker translates to: ”New! THE MASK OF FREEDOM! Salutations from the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces to sons of the beloved nation. Now available for an unlimited period of time.”]

Luckily, I was released on the same day with no charges whatsoever pressed by Military Prosecution. This, I believe, came as a result of quick and vast external pressure that manifested from the internet community, human rights groups, the press, and well, phone calls certain members of the military had received from “people high up.” Throughout this process, I happened to learn a few things.

1) We are our biggest enemies.

Many people I know would like to believe that my detainment by Military Police was part of a military crackdown on freedom of expression and general civil dismay towards Egypt’s so-called interim military rule. In all actuality, my detainment was a result of a long-lasting civil crackdown on freedom of expression.

The way it all went down was, as I was sticking one of the stickers onto a lamppost, two civilians stopped me and expressed their discomfort with it. This led to a little debate which other passersby felt the urge to partake in, which very quickly led to a big scene that involved a lot of shouting on the corner of a crossroads of two main downtown streets. This prompted the close-by traffic officer to use his walkie-talkie to call in Military Police. The reason Military Police was involved was that the regular law enforcement apparatus was entirely dysfunctional following “the revolution”, and martial law was virtually put into effect.

This, I think, highlights the core problem we face as a nation, and that is the culture of righting the wrong wrongs, and wronging what could be legitimate rights.

For example, it seems very acceptable in our culture to keep someone from expressing an opinion you may not agree with, but it isn’t so popular to keep someone from throwing trash on the street or blasting the volume of a Vespa-mounted stereo. This is especially odd to me, because it would seem to me that the act of throwing trash on the street would cause more direct discomfort to a another person than a sticker that criticizes the country’s governing body.

Some would disagree with me and point out that if such criticism were left unchallenged, it would lead to even more popular dismay towards the military body, which could possibly spark mass protests and strikes, which in turn could lead to a political situation that would make your lifestyle quite uncomfortable.

This very unrealistic roundabout argument can easily be invalidated by the facts surrounding my detainment. Although the Mask of Freedom was originally unleashed upon the inter-web on May 19th, it only spread on May 26th within hours of word of my arrest spreading across social networks. It very quickly got picked up by Al Ahram Online, Al Shorouk News, The Daily News Egypt, The Christian Science Monitor, and even television (local and CNN). As a result of my arrest, the image was vastly spread in less than 24 hours. The irony is that the very image that the civilian halted me for, to keep me from spreading, garnered even more exposure only because he stopped me.

More importantly, did the spreading of the image negatively affect that person’s life? I can assure you, this person very likely wakes up in the same bed, eats the same food, and most probably has the same job. Knowing so, I wonder if he still thinks it was worthwhile to keep me from putting up those stickers.

I sincerely believe that if he would instead put that same energy into keeping someone from littering the streets or chronically honking a car horn, his life would instantly improve, and he would most certainly feel the difference.

2) We are all but vessels.

A couple of friends of mine were putting up the same sticker in a different part of town when they, too, were halted by civilians. As the crowd of civilians grew, my friends were accused of being foreign spies, plotting against the nation, disrupting the peace, and all kinds of emotionally-charged things, until finally a police officer showed up, examined the sticker for 30 seconds before saying “What’s the big deal? Freedom.”

What was a very vocally disgruntled crowd less than a minute ago all of a sudden proceeded to face my two friends with smiles and ask if they could have some free stickers.

So this raises the question: Were they against the sticker because they morally believed it was wrong, or simply because they felt the need to take it upon themselves to do what was socially perceived as right?

I think the latter is correct, because if they had truly believed in the righteousness of their cause, they would’ve firmly opposed the police officer’s ruling. They didn’t and that gives me the impression that this urge to censor the sticker comes from a less-entrenched external source than moral intuition. This is essentially true, as it is no secret that the military has been using state TV and official newspapers to propagate the importance of the military’s role as authority in the country, and spread paranoia in regards to “foreign agendas” and peace-hating troublemakers.

This is a clear indication of how we, as people, are so easy to sway based on the ideas we are fed. As such, the direction taken by humanity at large is frighteningly easy to control. Which brings me to the next point.

3) We all need a crusade.

I was having a chat with film director Amr Salama the other day about this notion of humanity as an easily controllable vessel. I told him how I imagined a world where all these very influential media resources used to propagate fear and paranoia would instead be used to promote things like empowerment, liberty, honor, dignity, creative freedom and social justice. Salama argued that tapping into humanity’s dark side is a lot easier than tapping into humanity’s bright side. Upon examining historical events, this theory becomes eerily true. Peoples’ conviction with things such as racial or sexual equality has been moving at a much slower pace than peoples’ tendency to fear and attack a race or unfamiliar culture.

Essentially, people will always need a crusade. Even when attempting to sell the idea of doing something inherently good, it will need to be packaged in a fear-driven crusade for it to work. It’s easier for people to be against something than for something.

For example, the only way to get masses of people to care about the environment would be to promote the fear of global warming. People are driven by being against environmental destruction, rather than being for environmental prosperity.

4) It is important to transcend from the digital to the physical.

There is great value in spreading ideas over the internet, even if these ideas remain represented in the digital dimension of the world. As long as these ideas are exposed to people, these ideas will have great value. However, as soon as an idea takes on a more physical form, its impact on unsuspecting viewers enormously multiplies. This is apparent when comparing between the impact of the Mask of Freedom on May 19, when all I did was post it online, and its impact on May 26, when I decided to go down and take it to the streets.

5) Niceness does not necessarily mean goodness.

They were very nice to me at the military’s prosecution headquarters. I was served soda, Nescafe, and engaged in conversations with smiling military men. The content of these conversations, however, made it very clear to me that these people do not usually act out of goodness, but quite the contrary. An example would be when they attacked the tents in Tahrir and pulled out men and women who might’ve allegedly engaged in sexual activities, the military’s actions seem to have been motivated by a kind of malevolence, rather than doing a good deed. The same arguably applies to when they arrest criminals. It seems to stem from the desire to beat the shit out of someone rather than simply keep someone from committing a crime.

I got this sense when discussing widely agreed upon basic human rights that these officers find to be absurd. They find it absolutely legitimate to cuss and slap-around criminals during their arrest rather than limiting the act of the arrest to simply making the arrest. I find this completely disturbing, because as military personnel, one would expect them to have an understanding of these sort of rights that would not only apply to civil criminals but even prisoners of war. But respect for other human beings is not why people take to having a gun for a living.

However nice these men may be, they do not act upon goodness. The same could apply to a man like Mubarak his, who is said to be quite nice and personable around those he speaks to. His actions as a 30-year-long ruler of Egypt, on the other hand, show him to be anything but “good.”

6) Old men in uniform will never understand young boys in shorts.

I won’t get into the absurdity of my shorts and long hair being a topic of debate and discussion among the Old Men in Uniform, but I would like to point out how baffled these men were by the involvement of a young man in activities that were not backed by “organizations” or power-driven aspirations.

One of the questions directed towards me during the friendly interrogation was whether I was a member of the 6th-of-April Movement or Revolutionary Youth Coalition. When I answered that I was part of neither, the next logical question they asked was if I had been paid by someone to put up the Mask of Freedom stickers across town.

These Old Men in Uniform clearly cannot fathom the idea of a someone going around town to express something backed by nothing other than personal motivation. Sometimes young people tend to do things they believe in with no aspirations for power, money, or fame. The fact that these men do not understand that, I feel, is very dangerous and quite sad.

7) The Military “manages.

When debating whether or not the military is fit to “rule the nation,” a common argument brought up is that the military knows how to “manage”. It simply knows how to deal with situations. This very notion was made clear to me when inside the office of a high ranking officer at Military Prosecution Headquarters, I couldn’t help but notice the… air conditioning unit.

Yes, the air conditioning unit, which was an old model dating back to… maybe the late 80’s or early 90’s, was working very well. The room was definitely cool, but in accomplishing that, not only did we have to deal with the loud clunky noises of what sounded like a very exhausted machine, but the officer had set up a fan right in front of the unit to better spread the cool air around the room.

So instead of properly fixing the air conditioning unit or installing a more up-to-date device that might sound quieter and efficiently distribute the cool air around the room and most likely require less electricity to do its job, the army people thought it would be more practical to use the old unit and consume more electricity on the additional fan while at it.

This, I feel, has been the military’s strategy in managing the entire country since the Liberated Officers’ coup of 1952. As long as things work, regardless of inefficiency or social/psychological discomfort, they let it be.

Which is exactly why military personnel should be stripped from anything involving government.

--