Making the Intangible Tactile

Words + Non-fiction + Talk

2018.03.19

Claremont, CA

Scripps College Frederic W. Goudy Lecture, Spring 2018

Let’s get one thing straight: I’m not a printmaker, nor am I a bookmaker. I might’ve cranked the lever on a letterpress machine two, maybe three times. Which makes even first year students at this here institution far more knowledgeable about printmaking than I can ever hope to be. You are probably a lot more clever as well, because anybody who goes off to study things like printmaking and bookbinding in the year 2018 is likely wise enough to avoid the manipulation of today’s mass media, which seems far too taken by the virtual and augmented. Regardless of how useless these technologies have proven to be so far.

But let’s not forget that when printmaking first came into existence, it too was considered “mass media”. A new and revolutionary way to share ideas with a great many people.

Before Gutenberg printed bibles using movable type in 15th century Europe, there was the movable type invented by Pi Sheng in 11th century China. A detailed description of Sheng’s invention was described in Shen Kuo’s THE DREAM POOL ESSAYS, a seminal work that covered everything from astronomy, geology, and natural phenomena to architecture, philosophy, and even UFO sightings.

Some might find it surprising that this massive book was printed using tried-and-true woodblock methods rather than the new emerging technology of movable type, but I don’t think its weird at all. After all, we still shoot movies on traditional film even with the advent of Virtual Reality. And we still walk into brick-and-mortar stores to buy books printed on paper, even when armed with the power to download them onto our more convenient Kindles. Not to mention the comeback of Vinyl, which absolutely no one could’ve anticipated.

What this tells us is that the advent of one technology doesn’t necessarily have to spell the end of an older one. There’s room for coexistence, there’s room for variety.

Many will tell you that printmaking began with block-printing in the Far East, and they wouldn’t be wrong. But prior to woodblocks there was the stamp or seal. Evidence points to cylinder seals originating in Mesopotamia around 7000 years BC. Often carved out of stone, these seals would be rolled onto soft clay, leaving an impression that could be replicated an endless number of times.

![]()

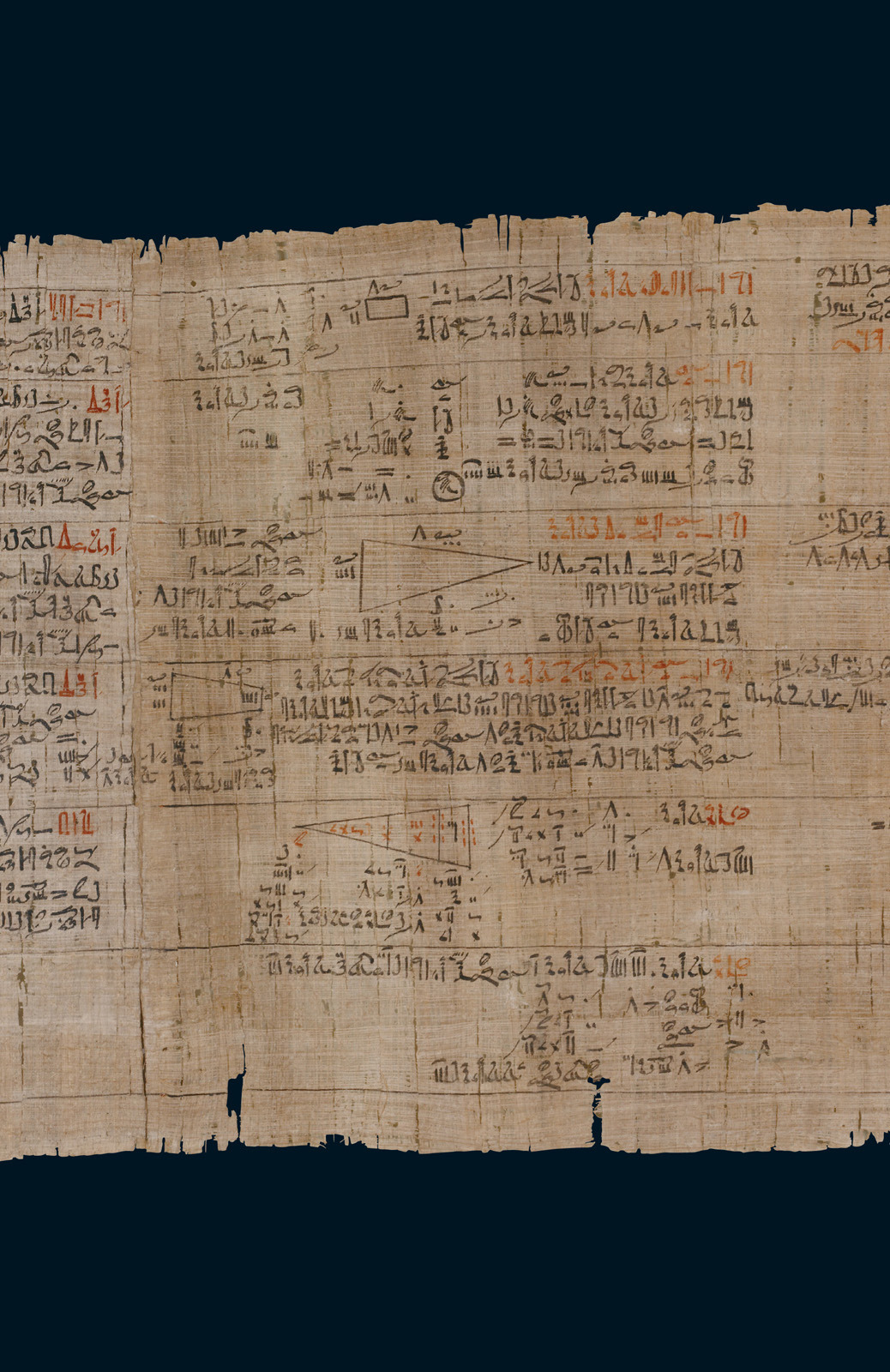

Seals dating back to Ancient Egypt were also found. Egypt is also where the art of stenciling was common practice. Hieroglyphs were stenciled onto stone walls, which were then chiseled by sculptors. An ingenious method that allowed for the speedy reproduction of information without skimping on the tactile qualities of 3-dimensional materiality. But perhaps, the greatest mass media device invented at the time was likely Egyptian paper, what the Greeks called: papyrus, which was produced as early as 3000 BC if not earlier.

![]()

A lot of craft and labor went into the making of papyrus, which made it valuable. So valuable that a scribe would not be allowed to write on papyrus prior to first spending several years honing his craft on discarded pieces of wood and shards of pottery. Once a scribe was ready, he or she would use papyrus for religious texts, official documents, letters and love poems, erotica, technical manuals, record keeping, spells and medical texts as well as, rebellion.

![]()

The image of seated mouse draped in fine linen being serviced by wild cats is a fine example of rebellion in Ancient Egypt. So powerful is this satirical image that it is immediately understood regardless of language, culture, place, or time. The prey ruling over the hunter. The hunter serving its prey.

It should come as no surprise that this fragment is dated back to the 19th dynasty, between 1295 and 1186 BC. Which coincides with the first known strike in recorded history - carried out by the artisans who worked on the tombs in the Valley of the Kings. These artists knew they were more powerful than kings and queens and shamans and aristocracy. They knew they were more powerful because it was their artwork that propped up regimes and made legends out of ordinary men. They knew that they were the cats in this story, and their rulers no more than mice.

This rebellion must’ve been organized, or at the very least, significantly infectious, because we find variations of this same image surviving on more than just one fragment, all dating to the exact same period.

![]()

What we’re looking at here, may be the earliest surviving form of the protest flyer, or even… the meme.

This is also significant because the Ancient Egyptians believed that the act of writing and drawing was no less than magic. That by putting a rather abstract thought in writing on a tangible object in the physical world was a way of making that thought become reality.

Which is perhaps why we find sculptures of scribes carved out of ever-lasting stone, a material usually reserved for the statues of gods and pharaohs.

![]()

I think about this often. About the special power of materializing ideas, of putting them out into the world, physically. I think it was 2011 when I started thinking about it seriously, when I created this image known as the Mask of Freedom. Egyptian dictator Hosni Mubarak was recently ousted, and the military took over, promising it would only be temporary. A transitional period in which the military oversaw the country’s transformation to a legitimate democracy. Referendums were held and people went out to vote in unprecedented numbers. Inspiring montages flickered on television screens and proud patriotic music took over the airwaves. The ushering of Egypt’s newfound democracy was on everyone’s lips, with the role played by the country’s honorable military never going unmentioned. It seemed like… a good idea to question that. Hence the Mask of Freedom, with accompanying text reading: “NEW! The Mask of Freedom! With salutations from the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces to sons of the beloved nation. Now available for an unlimited period of time.”

![]()

I first posted the image online, and it got its generous portion of likes and shares and what have you. It was all good, but then… about a week or two later, I hit the streets armed with stickers of the image and proceeded to put them up on lampposts around Downtown Cairo. And within an hour, I was arrested.

Luckily, I still had Twitter on my phone back then (I don’t anymore), and I was able to tweet about it before getting thrown in the back of a police car. The reaction to this was something akin to Kim Kardashian’s ass breaking the internet, except… instead of Kim’s ass, it was the Mask of Freedom.

Within hours, thousands of people changed their profile pictures to the image of the Mask. And Cairo’s very acute activist community managed to stage a protest where I was taken for questioning. Before I even got there. And they were armed with fresh printouts of the Mask of Freedom, a hi-res image of which was already available online. And within hours, I was released without charge.

![]()

That wasn’t the end of The Mask of Freedom. Within two days, bootlegged T-shirts sporting the mask were being sold in Tahrir square. In fact, different versions of the same shirt were going around, and the image was seen often at protests over the next couple years.

![]()

This is the difference between putting a picture on the internet and giving it a physical manifestation in the real world. The internet, believe it or not, isn’t as important as some make it out to be. I keep coming across college art magazines where students frequently talk about the power of clicks and “engaging content”, and it is one of the saddest, most disheartening things I’ve ever seen. As someone who has participated firsthand in a revolution described by US media as a “social media uprising”, let me tell ya: online activism is bullshit. Egypt’s dictator would have never been ousted had people not taken to the streets and occupied public squares, and I would’ve never been released from military-police custody had activists not showed up at their doorstep.

Even the term “online activism” is ridiculous. It’s a little like saying “telephone activism”. There’s no such thing, it’s just a communication tool. Sure, it’s a pretty good one, but a rather pointless one if what is being communicated does not seep into the physical world in some way or function.

Realizing the rather versatile applications of the Mask of Freedom, in that--much like the ancient Egyptian image of mouse ruling over cats--it could work in a range of situations regardless of time, place, or culture, I found myself using it more than once.

Poland, 2012 - After joining the EU, Poland’s market really opened up to big multinational corporations. And after years of suffering under soviet dictatorship which lasted til 1989, you could now see the Polish embracing consumerist culture with intense fervor. My response was to use the Mask of Freedom in a stencil on a wall in Katowice, historically known to be a big mining town in Poland. Hence the figure equipped with mining tools, while clad in Gap, Adidas, and Converse.

![]()

The text in Polish reads, very simply: “Beware the Mask of Freedom.”

Fast forward to 2015, and the Mask of Freedom reemerges as a very applicable American critique, in a 3-color screenprint on wood at a solo exhibition at Leila Heller Gallery in New York City.

![]()

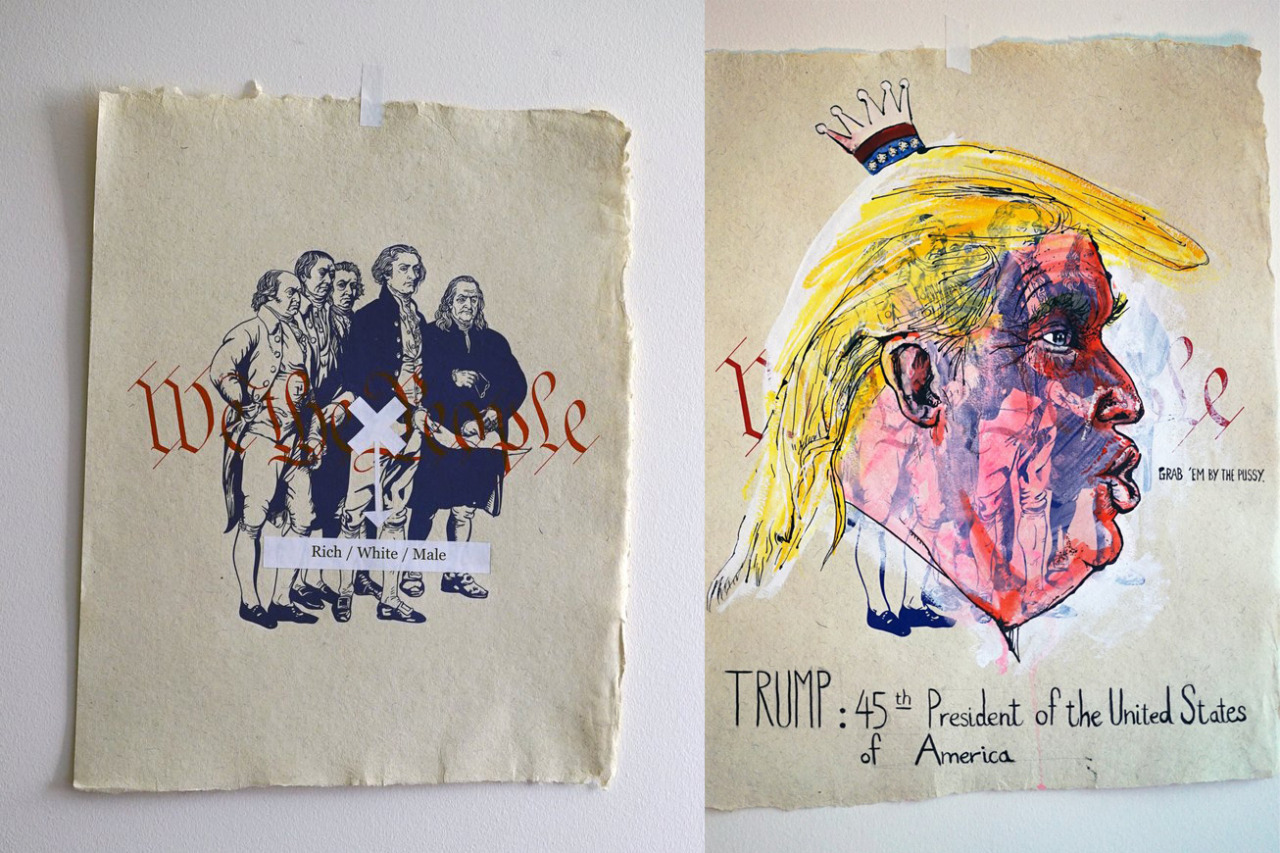

Of course, having come from a very old place, where dynasties have fallen, and others have risen, where Gods were no longer worshiped in favor of other Gods, and where culture has shifted and changed and altered more than once, I find it quite easy to look at everything with a critical eye, whether they be old… established, often deemed unquestionable things… or new.

![]()

Of course, as much as I’d like to, I don’t always get to do this sort of work. The unfortunate reality of being a working artist is that every so often you’re gonna have to take on commissions. One such commission was a sort-of art-video I did for Irish rock band, U2. This was part of a big campaign where they got 11 artists to do visual companion pieces to songs from their latest album. The band had stated that their inspiration for this particular album, Songs of Innocence, was the punk rock of the 70’s. And in thinking about that, it occurred to me that music videos weren’t yet a popular artform in the 70’s, and one’s visual experience of a band pretty much relied on the artwork on record sleeves and gig posters. So I thought why not make a video made up entirely of posters. This would also bring a very physical, very tactile quality to the video which I thought would be cool.

Okay, I have one last project I’d like to talk to you about. For a museum in Germany, I was asked to do an exhibition based on my current work-in-progress. A sci-fi graphic novel titled THE SOLAR GRID. Now I didn’t want to just take pages from the graphic novel and display them on the wall. It’s really not how the pages are meant to be experienced. They’re meant to be in a book that you could curl up with. And I really didn’t think it would make for a very compelling exhibition. What I wanted to do was create something specific to the museum experience. Not something meant for a book, and not something meant for the internet, but something really specific to entering into a museum space.

The premise of the graphic novel is that, after a major environmental catastrophe on a global scale, a lot of people leave Earth and settle on Mars. Over time, Earth becomes a de facto factory for Mars, exporting goods that are produced in solar-powered factories that never stop. This is made possible by a network of satellites, called The Solar Grid, that orbit the planet and keep it basked in eternal daylight. Effectively eliminating night on Earth.

Not everyone has migrated to Mars. In fact, most people haven’t. And they are left on a nightless Earth to suffer the consequences. Not just that, but they have the waste that Mars sends back to deal with.

So, there are a lot of somewhat abstract ideas here. Ideas that I wanted to bring to the museum’s space in a tangible way. The result was this installation.

![]()

So we built this room, and covered it in blown up panels from the graphic novel. This particular scene shows the sun setting, and then the sky lighting up with a great many smaller suns. And where there would’ve been another panel from the book, instead you have actual light blasting out of the room. Once inside the room, you see the walls covered in all the waste that the characters in the book would have to go through to survive. And right above your head, the ceiling is covered with these very harsh overhead lights, giving you a bit of the actual experience of being within the world of the graphic novel.

![]()

Now you’ll notice that all the examples I’ve cited here show work where the form and the content are closely related. I first think of an idea, and then I figure out the form it should take.

A lot of the time I come across book-arts and printmaking where the materials used are the extent of the artist’s idea. Where, rather than… the form an artwork takes being informed by an idea, the tools themselves become the idea. Where there’s an almost kind of fetishization that this is a letterpress on top of a screenprint or whatever. Please don’t do that.

Remember that not everything written in verse is poetry, and not everything covered in paint is a painting. What is being expressed is what truly elevates something to a work of art. How it is expressed is of course equally important. But before you get there, you must first consider what it is that needs expression, that demands expression.

That is your starting point.

Because that is what makes you unique, what makes you powerful. More powerful than kings or pharoahs or presidents. More powerful than CEOs or advertising executives or even Kim Kardashian. Remember that. Remember that every time you set pencil to paper–or even stylus to tablet–because that line you draw… has the potential to change the world. Every time.

Good luck.

Let’s get one thing straight: I’m not a printmaker, nor am I a bookmaker. I might’ve cranked the lever on a letterpress machine two, maybe three times. Which makes even first year students at this here institution far more knowledgeable about printmaking than I can ever hope to be. You are probably a lot more clever as well, because anybody who goes off to study things like printmaking and bookbinding in the year 2018 is likely wise enough to avoid the manipulation of today’s mass media, which seems far too taken by the virtual and augmented. Regardless of how useless these technologies have proven to be so far.

But let’s not forget that when printmaking first came into existence, it too was considered “mass media”. A new and revolutionary way to share ideas with a great many people.

Before Gutenberg printed bibles using movable type in 15th century Europe, there was the movable type invented by Pi Sheng in 11th century China. A detailed description of Sheng’s invention was described in Shen Kuo’s THE DREAM POOL ESSAYS, a seminal work that covered everything from astronomy, geology, and natural phenomena to architecture, philosophy, and even UFO sightings.

Some might find it surprising that this massive book was printed using tried-and-true woodblock methods rather than the new emerging technology of movable type, but I don’t think its weird at all. After all, we still shoot movies on traditional film even with the advent of Virtual Reality. And we still walk into brick-and-mortar stores to buy books printed on paper, even when armed with the power to download them onto our more convenient Kindles. Not to mention the comeback of Vinyl, which absolutely no one could’ve anticipated.

What this tells us is that the advent of one technology doesn’t necessarily have to spell the end of an older one. There’s room for coexistence, there’s room for variety.

Many will tell you that printmaking began with block-printing in the Far East, and they wouldn’t be wrong. But prior to woodblocks there was the stamp or seal. Evidence points to cylinder seals originating in Mesopotamia around 7000 years BC. Often carved out of stone, these seals would be rolled onto soft clay, leaving an impression that could be replicated an endless number of times.

Seals dating back to Ancient Egypt were also found. Egypt is also where the art of stenciling was common practice. Hieroglyphs were stenciled onto stone walls, which were then chiseled by sculptors. An ingenious method that allowed for the speedy reproduction of information without skimping on the tactile qualities of 3-dimensional materiality. But perhaps, the greatest mass media device invented at the time was likely Egyptian paper, what the Greeks called: papyrus, which was produced as early as 3000 BC if not earlier.

A lot of craft and labor went into the making of papyrus, which made it valuable. So valuable that a scribe would not be allowed to write on papyrus prior to first spending several years honing his craft on discarded pieces of wood and shards of pottery. Once a scribe was ready, he or she would use papyrus for religious texts, official documents, letters and love poems, erotica, technical manuals, record keeping, spells and medical texts as well as, rebellion.

The image of seated mouse draped in fine linen being serviced by wild cats is a fine example of rebellion in Ancient Egypt. So powerful is this satirical image that it is immediately understood regardless of language, culture, place, or time. The prey ruling over the hunter. The hunter serving its prey.

It should come as no surprise that this fragment is dated back to the 19th dynasty, between 1295 and 1186 BC. Which coincides with the first known strike in recorded history - carried out by the artisans who worked on the tombs in the Valley of the Kings. These artists knew they were more powerful than kings and queens and shamans and aristocracy. They knew they were more powerful because it was their artwork that propped up regimes and made legends out of ordinary men. They knew that they were the cats in this story, and their rulers no more than mice.

This rebellion must’ve been organized, or at the very least, significantly infectious, because we find variations of this same image surviving on more than just one fragment, all dating to the exact same period.

What we’re looking at here, may be the earliest surviving form of the protest flyer, or even… the meme.

This is also significant because the Ancient Egyptians believed that the act of writing and drawing was no less than magic. That by putting a rather abstract thought in writing on a tangible object in the physical world was a way of making that thought become reality.

Which is perhaps why we find sculptures of scribes carved out of ever-lasting stone, a material usually reserved for the statues of gods and pharaohs.

I think about this often. About the special power of materializing ideas, of putting them out into the world, physically. I think it was 2011 when I started thinking about it seriously, when I created this image known as the Mask of Freedom. Egyptian dictator Hosni Mubarak was recently ousted, and the military took over, promising it would only be temporary. A transitional period in which the military oversaw the country’s transformation to a legitimate democracy. Referendums were held and people went out to vote in unprecedented numbers. Inspiring montages flickered on television screens and proud patriotic music took over the airwaves. The ushering of Egypt’s newfound democracy was on everyone’s lips, with the role played by the country’s honorable military never going unmentioned. It seemed like… a good idea to question that. Hence the Mask of Freedom, with accompanying text reading: “NEW! The Mask of Freedom! With salutations from the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces to sons of the beloved nation. Now available for an unlimited period of time.”

I first posted the image online, and it got its generous portion of likes and shares and what have you. It was all good, but then… about a week or two later, I hit the streets armed with stickers of the image and proceeded to put them up on lampposts around Downtown Cairo. And within an hour, I was arrested.

Luckily, I still had Twitter on my phone back then (I don’t anymore), and I was able to tweet about it before getting thrown in the back of a police car. The reaction to this was something akin to Kim Kardashian’s ass breaking the internet, except… instead of Kim’s ass, it was the Mask of Freedom.

Within hours, thousands of people changed their profile pictures to the image of the Mask. And Cairo’s very acute activist community managed to stage a protest where I was taken for questioning. Before I even got there. And they were armed with fresh printouts of the Mask of Freedom, a hi-res image of which was already available online. And within hours, I was released without charge.

That wasn’t the end of The Mask of Freedom. Within two days, bootlegged T-shirts sporting the mask were being sold in Tahrir square. In fact, different versions of the same shirt were going around, and the image was seen often at protests over the next couple years.

This is the difference between putting a picture on the internet and giving it a physical manifestation in the real world. The internet, believe it or not, isn’t as important as some make it out to be. I keep coming across college art magazines where students frequently talk about the power of clicks and “engaging content”, and it is one of the saddest, most disheartening things I’ve ever seen. As someone who has participated firsthand in a revolution described by US media as a “social media uprising”, let me tell ya: online activism is bullshit. Egypt’s dictator would have never been ousted had people not taken to the streets and occupied public squares, and I would’ve never been released from military-police custody had activists not showed up at their doorstep.

Even the term “online activism” is ridiculous. It’s a little like saying “telephone activism”. There’s no such thing, it’s just a communication tool. Sure, it’s a pretty good one, but a rather pointless one if what is being communicated does not seep into the physical world in some way or function.

Realizing the rather versatile applications of the Mask of Freedom, in that--much like the ancient Egyptian image of mouse ruling over cats--it could work in a range of situations regardless of time, place, or culture, I found myself using it more than once.

Poland, 2012 - After joining the EU, Poland’s market really opened up to big multinational corporations. And after years of suffering under soviet dictatorship which lasted til 1989, you could now see the Polish embracing consumerist culture with intense fervor. My response was to use the Mask of Freedom in a stencil on a wall in Katowice, historically known to be a big mining town in Poland. Hence the figure equipped with mining tools, while clad in Gap, Adidas, and Converse.

The text in Polish reads, very simply: “Beware the Mask of Freedom.”

Fast forward to 2015, and the Mask of Freedom reemerges as a very applicable American critique, in a 3-color screenprint on wood at a solo exhibition at Leila Heller Gallery in New York City.

Of course, having come from a very old place, where dynasties have fallen, and others have risen, where Gods were no longer worshiped in favor of other Gods, and where culture has shifted and changed and altered more than once, I find it quite easy to look at everything with a critical eye, whether they be old… established, often deemed unquestionable things… or new.

Of course, as much as I’d like to, I don’t always get to do this sort of work. The unfortunate reality of being a working artist is that every so often you’re gonna have to take on commissions. One such commission was a sort-of art-video I did for Irish rock band, U2. This was part of a big campaign where they got 11 artists to do visual companion pieces to songs from their latest album. The band had stated that their inspiration for this particular album, Songs of Innocence, was the punk rock of the 70’s. And in thinking about that, it occurred to me that music videos weren’t yet a popular artform in the 70’s, and one’s visual experience of a band pretty much relied on the artwork on record sleeves and gig posters. So I thought why not make a video made up entirely of posters. This would also bring a very physical, very tactile quality to the video which I thought would be cool.

Okay, I have one last project I’d like to talk to you about. For a museum in Germany, I was asked to do an exhibition based on my current work-in-progress. A sci-fi graphic novel titled THE SOLAR GRID. Now I didn’t want to just take pages from the graphic novel and display them on the wall. It’s really not how the pages are meant to be experienced. They’re meant to be in a book that you could curl up with. And I really didn’t think it would make for a very compelling exhibition. What I wanted to do was create something specific to the museum experience. Not something meant for a book, and not something meant for the internet, but something really specific to entering into a museum space.

The premise of the graphic novel is that, after a major environmental catastrophe on a global scale, a lot of people leave Earth and settle on Mars. Over time, Earth becomes a de facto factory for Mars, exporting goods that are produced in solar-powered factories that never stop. This is made possible by a network of satellites, called The Solar Grid, that orbit the planet and keep it basked in eternal daylight. Effectively eliminating night on Earth.

Not everyone has migrated to Mars. In fact, most people haven’t. And they are left on a nightless Earth to suffer the consequences. Not just that, but they have the waste that Mars sends back to deal with.

So, there are a lot of somewhat abstract ideas here. Ideas that I wanted to bring to the museum’s space in a tangible way. The result was this installation.

So we built this room, and covered it in blown up panels from the graphic novel. This particular scene shows the sun setting, and then the sky lighting up with a great many smaller suns. And where there would’ve been another panel from the book, instead you have actual light blasting out of the room. Once inside the room, you see the walls covered in all the waste that the characters in the book would have to go through to survive. And right above your head, the ceiling is covered with these very harsh overhead lights, giving you a bit of the actual experience of being within the world of the graphic novel.

Now you’ll notice that all the examples I’ve cited here show work where the form and the content are closely related. I first think of an idea, and then I figure out the form it should take.

A lot of the time I come across book-arts and printmaking where the materials used are the extent of the artist’s idea. Where, rather than… the form an artwork takes being informed by an idea, the tools themselves become the idea. Where there’s an almost kind of fetishization that this is a letterpress on top of a screenprint or whatever. Please don’t do that.

Remember that not everything written in verse is poetry, and not everything covered in paint is a painting. What is being expressed is what truly elevates something to a work of art. How it is expressed is of course equally important. But before you get there, you must first consider what it is that needs expression, that demands expression.

That is your starting point.

Because that is what makes you unique, what makes you powerful. More powerful than kings or pharoahs or presidents. More powerful than CEOs or advertising executives or even Kim Kardashian. Remember that. Remember that every time you set pencil to paper–or even stylus to tablet–because that line you draw… has the potential to change the world. Every time.

Good luck.