Zine El-Arab

Publication

2011.11 + 2012.02

Amman, JO + Cairo, EG

ZINE EL-ARAB is a zine I launched and co-edited with Nizar Alkhairy. Only two issues were ever produced, the first in late 2011 and the second in early 2012.

A couple copies have recently (August 2019) made their way to the collections of the Bavarian State Library and Archive Artist Publications, both located in Munich, so I thought it might be a good time to revisit how the zine came about and why it was discontinued.

If you know me at all, then you know I like to operate where I see vacuums in the culture. Zine El-Arab came about precisely for that reason. This was 2011, a time of great revolutionary upheaval that started in Tunisia, spilled over into Egypt, and kind of spread from there not just in the region but halfway across the world.

By late 2011, there was really no denying the ripples of change pulsating through Cairo. It was evident on the streets, in music, conversations, at art galleries, on television, it was everywhere. But I was growing frustrated that there didn’t seem to be any regular publication that featured the voices of dissent that were otherwise all around you. It felt like there was a rift between everyday voices and what was being published, and how cool would it be if there were at least one? Especially if it were a crude one.

The big kicker though was a residency that was offered to me by Makan in Amman (Jordan) where I got to meet Nizar Alkhairy and engaged with many other members of the local art/poetry/architecture/journalism scene, and that’s when I felt having a singular venue that can act as a vessel for all these voices from across multiple borders would not only be a good idea, but quite possibly a necessary one. Not just for the voices from Jordan or Egypt but across the entire Arab-speaking world if possible. And thus came Zine El-Arab, admittedly hyperbolically touted as the first pan-Arab zine. The vast majority of participants were from Jordan and Egypt, but it also received material from Palestine, Lebanon, Syria, and Qatar (I imagine its reach could have extended even further had it continued).

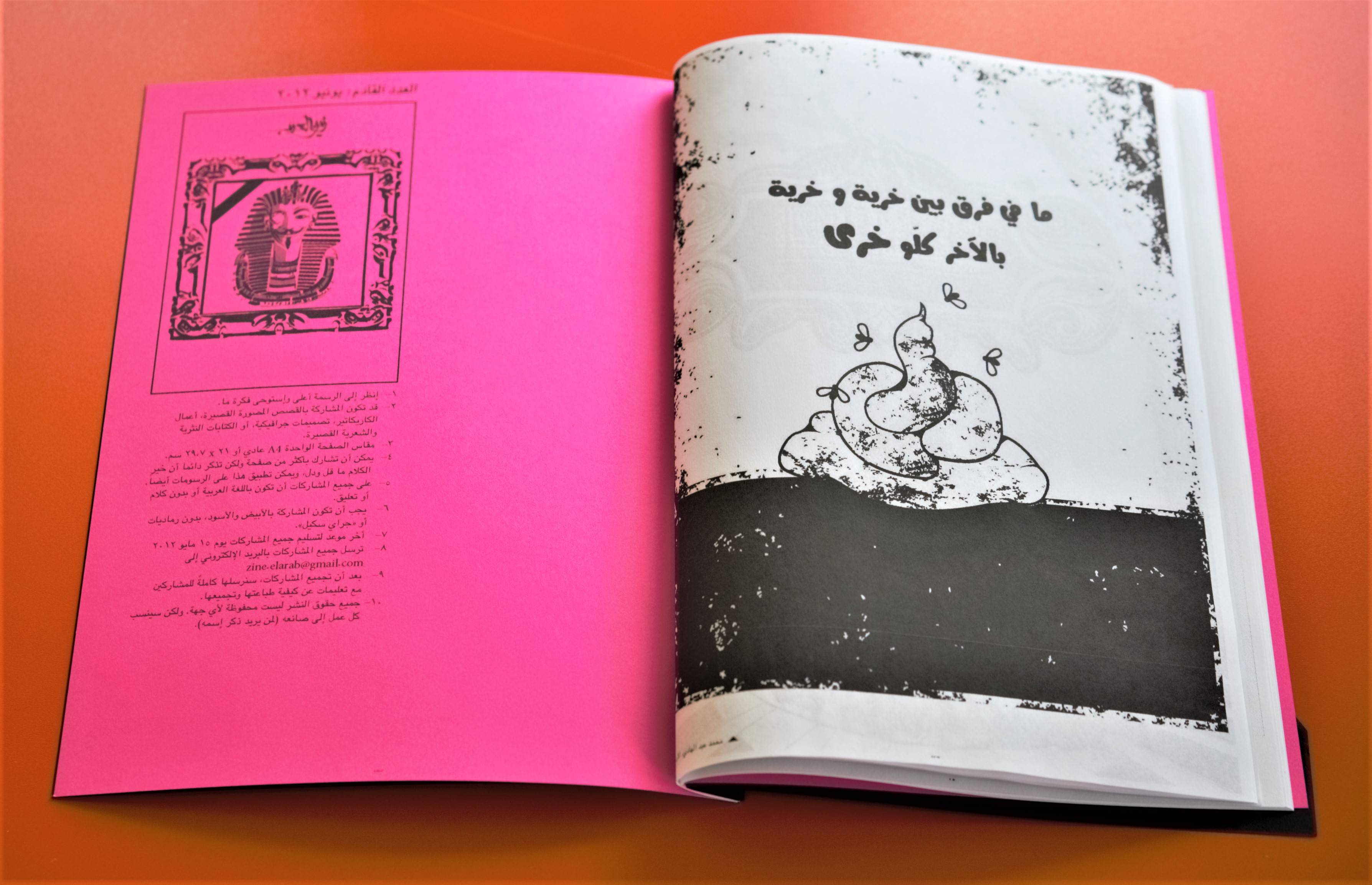

The formula was seemingly quite simple. The cover image (created by me) was posted on social media, inviting contributors from the Arab-speaking world to respond to it with either text or image (B&W only). Appropriate submissions would be selected and assembled into a digital zine which would be uploaded as a PDF with detailed instructions about printing and assembly. The idea was to decentralize not only the content, but the physical production of the zine as well, whereby contributors and readers could print their own copies and organically disseminate among their communities.

In reality, both issues had their “launch parties”, issue one at Makan in Jordan and issue two at the Townhouse Gallery in Cairo, which involved needing to print and assemble something like 100 copies for each launch.

One thing I wanted to do was to take advantage of the fact that each copy was technically individually printed and bound. So for issue #1 for example, there were instructions to paint the blood stain on the cover manually, and inside there was one page (adorned with multiple images) intended for print on adhesive-paper, whereby readers could cut out and use as stickers.

Issue #2′s cover — themed around racism and discrimination — was even more elaborate, comprised of essentially two covers with the first manually cut at a diagonal angle. The dialogue balloons were cut out and manually glued on, left blank to allow readers to write the text they wanted (with the original prompt acting as a thematic guide). And inside the issue there was one page printed on translucent paper, creating a kind-of-combined image with the page that comes right after (although, for the editions sent out to the Bavarian State Library and AAP, I had to illustrate that particular page by hand because the translucent paper kept jamming inside my printer!)

Although these very handmade aspects gave the zines a unique tactile quality, they become exhausting and impractical if you have to manually apply them to 100+ copies.

In the end, the zines were a fun experiment that without a doubt very much encapsulated the air of the time, and provided for a formidable venue for a selection of writers, artists, illustrators, and graphic designers to voice their thoughts.

It should be noted that there’s a little wordplay in the zine’s name. The word “zine” when written in Arabic is the same exact spelling as the word “zain”, roughly meaning “the best”. So Zine El-Arab not only suggests “the zine of the Arab” but it is simultaneously read as “the best of the Arab”.

Special thanks to Hussein Alazaat for the masthead calligraphy on both covers. And thanks to all the badass contributors on both issues: Bashar Humeidh, Amer Shumali, Abu Alfarag Bin Qareeb, Aram Tamenian, Kareem Gouda, Rebel Souly, Noha Ennab, Hashem Elkelesh, Michael Habib, Mahmoud Hafez, Islam Shabana, Ahmed Zaatari, Suzan Alwattar, Omar Okasha, Ahmed T.,Nancy Ibrahim, Damon Kowarsky, Mohammed Abdel Hady, Zeina Azouqa, Omnia Naguib, Saman S., Jacqueline George, Elkamouny, Batta Souda, and of course, Nidal Alkhairy.

And last but not least big thanks to Makan in Amman and the Townhouse Gallery in Cairo.

For PDF downloads:

Zine El Arab #1

Zine El Arab #2

A couple copies have recently (August 2019) made their way to the collections of the Bavarian State Library and Archive Artist Publications, both located in Munich, so I thought it might be a good time to revisit how the zine came about and why it was discontinued.

If you know me at all, then you know I like to operate where I see vacuums in the culture. Zine El-Arab came about precisely for that reason. This was 2011, a time of great revolutionary upheaval that started in Tunisia, spilled over into Egypt, and kind of spread from there not just in the region but halfway across the world.

By late 2011, there was really no denying the ripples of change pulsating through Cairo. It was evident on the streets, in music, conversations, at art galleries, on television, it was everywhere. But I was growing frustrated that there didn’t seem to be any regular publication that featured the voices of dissent that were otherwise all around you. It felt like there was a rift between everyday voices and what was being published, and how cool would it be if there were at least one? Especially if it were a crude one.

The big kicker though was a residency that was offered to me by Makan in Amman (Jordan) where I got to meet Nizar Alkhairy and engaged with many other members of the local art/poetry/architecture/journalism scene, and that’s when I felt having a singular venue that can act as a vessel for all these voices from across multiple borders would not only be a good idea, but quite possibly a necessary one. Not just for the voices from Jordan or Egypt but across the entire Arab-speaking world if possible. And thus came Zine El-Arab, admittedly hyperbolically touted as the first pan-Arab zine. The vast majority of participants were from Jordan and Egypt, but it also received material from Palestine, Lebanon, Syria, and Qatar (I imagine its reach could have extended even further had it continued).

The formula was seemingly quite simple. The cover image (created by me) was posted on social media, inviting contributors from the Arab-speaking world to respond to it with either text or image (B&W only). Appropriate submissions would be selected and assembled into a digital zine which would be uploaded as a PDF with detailed instructions about printing and assembly. The idea was to decentralize not only the content, but the physical production of the zine as well, whereby contributors and readers could print their own copies and organically disseminate among their communities.

In reality, both issues had their “launch parties”, issue one at Makan in Jordan and issue two at the Townhouse Gallery in Cairo, which involved needing to print and assemble something like 100 copies for each launch.

One thing I wanted to do was to take advantage of the fact that each copy was technically individually printed and bound. So for issue #1 for example, there were instructions to paint the blood stain on the cover manually, and inside there was one page (adorned with multiple images) intended for print on adhesive-paper, whereby readers could cut out and use as stickers.

Issue #2′s cover — themed around racism and discrimination — was even more elaborate, comprised of essentially two covers with the first manually cut at a diagonal angle. The dialogue balloons were cut out and manually glued on, left blank to allow readers to write the text they wanted (with the original prompt acting as a thematic guide). And inside the issue there was one page printed on translucent paper, creating a kind-of-combined image with the page that comes right after (although, for the editions sent out to the Bavarian State Library and AAP, I had to illustrate that particular page by hand because the translucent paper kept jamming inside my printer!)

Although these very handmade aspects gave the zines a unique tactile quality, they become exhausting and impractical if you have to manually apply them to 100+ copies.

In the end, the zines were a fun experiment that without a doubt very much encapsulated the air of the time, and provided for a formidable venue for a selection of writers, artists, illustrators, and graphic designers to voice their thoughts.

It should be noted that there’s a little wordplay in the zine’s name. The word “zine” when written in Arabic is the same exact spelling as the word “zain”, roughly meaning “the best”. So Zine El-Arab not only suggests “the zine of the Arab” but it is simultaneously read as “the best of the Arab”.

Special thanks to Hussein Alazaat for the masthead calligraphy on both covers. And thanks to all the badass contributors on both issues: Bashar Humeidh, Amer Shumali, Abu Alfarag Bin Qareeb, Aram Tamenian, Kareem Gouda, Rebel Souly, Noha Ennab, Hashem Elkelesh, Michael Habib, Mahmoud Hafez, Islam Shabana, Ahmed Zaatari, Suzan Alwattar, Omar Okasha, Ahmed T.,Nancy Ibrahim, Damon Kowarsky, Mohammed Abdel Hady, Zeina Azouqa, Omnia Naguib, Saman S., Jacqueline George, Elkamouny, Batta Souda, and of course, Nidal Alkhairy.

And last but not least big thanks to Makan in Amman and the Townhouse Gallery in Cairo.

For PDF downloads:

Zine El Arab #1

Zine El Arab #2